Linus:为何对象引用计数必须是原子的

(感谢网友 @我的上铺叫路遥 投稿)

Linus大神又在rant了!这次的吐槽对象是时下很火热的并行技术(parellism),并直截了当地表示并行计算是浪费所有人时间(“The whole “let’s parallelize” thing is a huge waste of everybody’s time.”)。大致意思是说乱序性能快、提高缓存容量、降功耗。当然笔者不打算正面讨论并行的是是非非(过于宏伟的主题),因为Linus在另一则帖子中举了对象引用计数(reference counting)的例子来说明并行的复杂性。

在Linus回复之前有人指出对象需要锁机制的情况下,引用计数的原子性问题:

Since it is being accessed in a multi-threaded way, via multiple access paths, generally it needs its own mutex — otherwise, reference counting would not be required to be atomic and a lock of a higher-level object would suffice.

由于(对象)通过多线程方式及多种获取渠道,一般而言它需要自身维护一个互斥锁——否则引用计数就不要求是原子的,一个更高层次的对象锁足矣。

而Linus不那么认为:

The problem with reference counts is that you often need to take them *before* you take the lock that protects the object data.

引用计数的问题在于你经常需要在对象数据上锁保护之前完成它。

The thing is, you have two different cases:

问题有两种情况:

– object *reference* 对象引用

– object data 对象数据

and they have completely different locking.

它们锁机制是完全不一样的。

Object data locking is generally per-object. Well, unless you don’t have huge scalability issues, in which case you may have some external bigger lock (extreme case: one single global lock).

对象数据保护一般是一个对象拥有一个锁,假设你没有海量扩展性问题,不然你需要一些外部大一点的锁(极端的例子,一个对象一个全局锁)。

But object *referencing* is mostly about finding the object (and removing/freeing it). Is it on a hash chain? Is it in a tree? Linked list? When the reference count goes down to zero, it’s not the object data that you need to protect (the object is not used by anything else, so there’s nothing to protect!), it’s the ways to find the object you need to protect.

但对象引用主要关于对象的寻找(移除或释放),它是否在哈希链,一棵树或者链表上。当对象引用计数降为零,你要保护的不是对象数据,因为对象没有在其它地方使用,你要保护的是对象的寻找操作。

And the lock for the lookup operation cannot be in the object, because – by definition – you don’t know what the object is! You’re trying to look it up, after all.

而且查询操作的锁不可能在对象内部,因为根据定义,你还不知道这是什么对象,你在尝试寻找它。

So generally you have a lock that protects the lookup operation some way, and the reference count needs to be atomic with respect to that lock.

因此一般你要对查询操作上锁,而且引用计数相对那个锁来说是原子的(译者注:查询锁不是引用计数所在的对象所有,不能保护对象引用计数,后面会解释为何引用计数变更时其所在对象不能上锁)。

And yes, that lock may well be sufficient, and now you’re back to non-atomic reference counts. But you usually don’t have just one way to look things up: you might have pointers from other objects (and that pointer is protected by the object locking of the other object), but there may be multiple such objects that point to this (which is why you have a reference count in the first place!)

当然这个锁是充分有效的,现在假设引用计数是非原子的,但你常常不仅仅使用一种方式来查询:你可能拥有其它对象的指针(这个指针又被其它对象的对象锁给保护起来),但同时还会有多个对象指向它(这就是为何你第一时间需要引用计数的理由)。

See what happens? There is no longer one single lock for lookup. Imagine walking a graph of objects, where objects have pointers to each other. Each pointer implies a reference to an object, but as you walk the graph, you have to release the lock from the source object, so you have to take a new reference to the object you are now entering.

看看会发生什么?查询不止存在一个锁保护。你可以想象走过一张对象流程图,其中对象存在指向其它对象的指针,每个指针暗含了一次对象引用,但当你走过这个流程图,你必须释放源对象的锁,而你进入新对象时又必须增加一次引用。

And in order to avoid deadlocks, you can not in the general case take the lock of the new object first – you have to release the lock on the source object, because otherwise (in a complex graph), how do you avoid simple ABBA deadlock?

而且为了避免死锁,你一般不能立即对新对象上锁——你必须释放源对象的锁,否则在一个复杂流程图里,你如何避免ABBA死锁(译者注:假设两个线程,一个是A->B,另一个B->;A,当线程一给A上锁,线程二给B上锁,此时两者谁也无法释放对方的锁)?

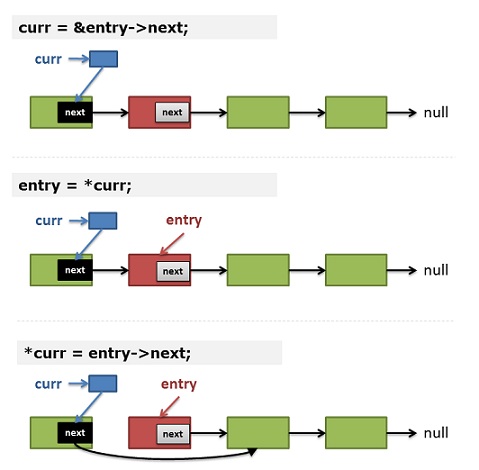

So atomic reference counts fix that. They work because when you move from object A to object B, you can do this:

原子引用计数修正了这一点,当你从对象A到对象B,你会这样做:

(a) you have a reference count to A, and you can lock A

对象A增加一次引用计数,并上锁。

(b) once object A is locked, the pointer from A to B is stable, and you know you have a reference to B (because of that pointer from A to B)

对象A一旦上锁,A指向B的指针就是稳定的,于是你知道你引用了对象B。

(c) but you cannot take the object lock for B (ABBA deadlock) while holding the lock on A

但你不能在对象A上锁期间给B上锁(ABBA死锁)。

(d) increment the atomic reference count on B

对象B增加一次原子引用计数。

(e) now you can drop the lock on A (you’re “exiting” A)

现在你可以扔掉对象A的锁(退出对象A)。

(f) your reference count means that B cannot go away from under you despite unlocking A, so now you can lock B.

对象B的原子引用计数意味着即使给A解锁期间,B也不会失联,现在你可以给B上锁。

See? Atomic reference counts make this kind of situation possible. Yes, you want to avoid the overhead if at all possible (for example, maybe you have a strict ordering of objects, so you know you can walk from A to B, and never walk from B to A, so there is no ABBA deadlock, and you can just lock B while still holding the lock on A).

看见了吗?原子引用计数使这种情况成为可能。是的,你想尽一切办法避免这种代价,比如,你也许把对象写成严格顺序的,这样你可以从A到B,绝不会从B到A,如此就不存在ABBA死锁了,你也就可以在A上锁期间给B上锁了。

But if you don’t have some kind of forced ordering, and if you have multiple ways to reach an object (and again – why have reference counts in the first place if that isn’t true!) then atomic reference counts really are the simple and sane answer.

但如果你无法做到这种强迫序列,如果你有多种方式接触一个对象(再一次强调,这是第一时间使用引用计数的理由),这样,原子引用计数就是简单又理智的答案。

If you think atomic refcounts are unnecessary, that’s a big flag that you don’t actually understand the complexities of locking.

如果你认为原子引用计数是不必要的,这就大大说明你实际上不了解锁机制的复杂性。

Trust me, concurrency is hard. There’s a reason all the examples of “look how easy it is to parallelize things” tend to use simple arrays and don’t ever have allocations or freeing of the objects.

相信我,并发设计是困难的。所有关于“并行化如此容易”的理由都倾向于使用简单数组操作做例子,甚至不包含对象的分配和释放。

People who think that the future is highly parallel are invariably completely unaware of just how hard concurrency really is. They’ve seen Linpack, they’ve seen all those wonderful examples of sorting an array in parallel, they’ve seen all these things that have absolutely no actual real complexity – and often very limited real usefulness.

那些认为未来是高度并行化的人一成不变地完全没有意识到并发设计是多么困难。他们只见过Linpack,他们只见过并行技术中关于数组排序的一切精妙例子,他们只见过一切绝不算真正复杂的事物——对真正的用处经常是非常有限的。

(译者注:当然,我无意借大神之口把技术宗教化。实际上Linus又在另一篇帖子中综合了对并行的评价。)

Oh, I agree. My example was the simple case. The really complex cases are much worse.

哦,我同意。我的例子还算简单,真正复杂的用例更糟糕。

I seriously don’t believe that the future is parallel. People who think you can solve it with compilers or programming languages (or better programmers) are so far out to lunch that it’s not even funny.

我严重不相信未来是并行的。有人认为你可以通过编译器,编程语言或者更好的程序员来解决问题,他们目前都是神志不清,没意识到这一点都不有趣。

Parallelism works well in simplified cases with fairly clear interfaces and models. You find parallelism in servers with independent queries, in HPC, in kernels, in databases. And even there, people work really hard to make it work at all, and tend to expressly limit their models to be more amenable to it (eg databases do some things much better than others, so DB admins make sure that they lay out their data in order to cater to the limitations).

并行计算可以在简化的用例以及具备清晰的接口和模型上正常工作。你发现并行在服务器上独立查询里,在高性能计算(High-performance computing)里,在内核里,在数据库里。即使如此,人们还得花很大力气才能使它工作,并且还要明确限制他们的模型来尽更多义务(例如数据库要想做得更好,数据库管理员得确保数据得到合理安排来迎合局限性)。

Of course, other programming models can work. Neural networks are inherently very parallel indeed. And you don’t need smarter programmers to program them either..

当然,其它编程模型倒能派上用场,神经网络(neural networking)天生就是非常并行化的,你不需要更聪明的程序员为之写代码。

参考资料

- Real World Technologies:Linus常去“灌水”的一个论坛,讨论未来机器架构(看名字就知道Linus技术偏好,及其之前对虚拟化技术(virtualization)的吐槽)

- 多线程程序中操作的原子性:解释为什么i++不是原子操作

- Concurrency Is Not Parallelism:Go语言之父Rob Pike幻灯片解释“并发”与“并行”概念上的区别